Abbas: Magnum photographer who chronicled religions, wars and the Iranian revolution

Dismissed in his country of birth, Iran, as a Bahai with an anti-Islam agenda, the photojournalist was an observer of what people across religions do in the name of God

In the 1970s, Abbas Attar shot The Greatest and, arguably, The Worst, winning international acclaim as a titan of photojournalism.

He was in Zaire in 1974 when Muhammad Ali was preparing for his Rumble in the Jungle with George Foreman.

That was one fight safe for Abbas – the name he used professionally – to shoot; no chance of getting caught in the crossfire like many of the war zones he covered.

He ducked bullets and dodged violence in Biafra, Bangladesh, Northern Ireland, Vietnam, the Middle East, Chile, Cuba, and South Africa.

Left-foot forward, the champ is gently jogging on the quarter of the canvas and ropes in view, or dancing as he would put it, as if propelled by the fans keeping him cool overhead.

There is on Ali’s face a hint of a grin and also of anxiety – the watching world attested to by a barely discernible row of people in the background. The expanse of the ceiling which takes up much of the frame makes him look oddly vulnerable and alone.

“I want to give the feeling that the people I photographed kept on doing whatever they were doing before I photographed them,” Abbas said. It was what he called a “suspended moment”.

In 1979 a menacing turbaned figure steps out of an Air France plane in Tehran – Abbas is back in his country of birth, which he left for Algeria aged eight, to chart its brewing revolution as “a historian of the present”.

Ayatollah Khomeini is flanked by concerned-looking bearded men wearing turbans. At the top of boarding stairs he holds his cloak together at his waist, one hand on the shoulder of a European pilot who is incongruously wearing sunglasses, and a smile.

Khomeini had been exiled by the Mohammad Reza Shah 14 years earlier and now the tables were turned: it was the dictator monarch’s turn to flee.

Speaking to the BBC last year, Abbas pointed out the portent he discerned in Khomeini’s severe gaze.

“You see the intensity of his look, the destiny of Iran is written there.”

As Abbas put it, the Ayatollah’s eyes seemed to say: “Wait until my feet hit the ground and then you will see”.

A young revolutionary, nose and mouth covered by a white cloth, grips an assault rifle in a morgue. Four pale, male torsos lie dead, legs out of view in the fridge. He looks nervous, as if they might rise. Generals, secret police, what did it matter, summary executions were not what Abbas had signed up for in supporting the ousting of the Shah.

That was a turning point, for Abbas and countless others. “I decided this revolution is not going to be mine anymore,” he said.

Abbas captures a “mullah in a car with a gun in his hand … somebody who is supposed to be religious, spiritual”.

In 1980, the image is used on the cover of his first book, Iran, La Revolution Confisquee (Confiscated Revolution).

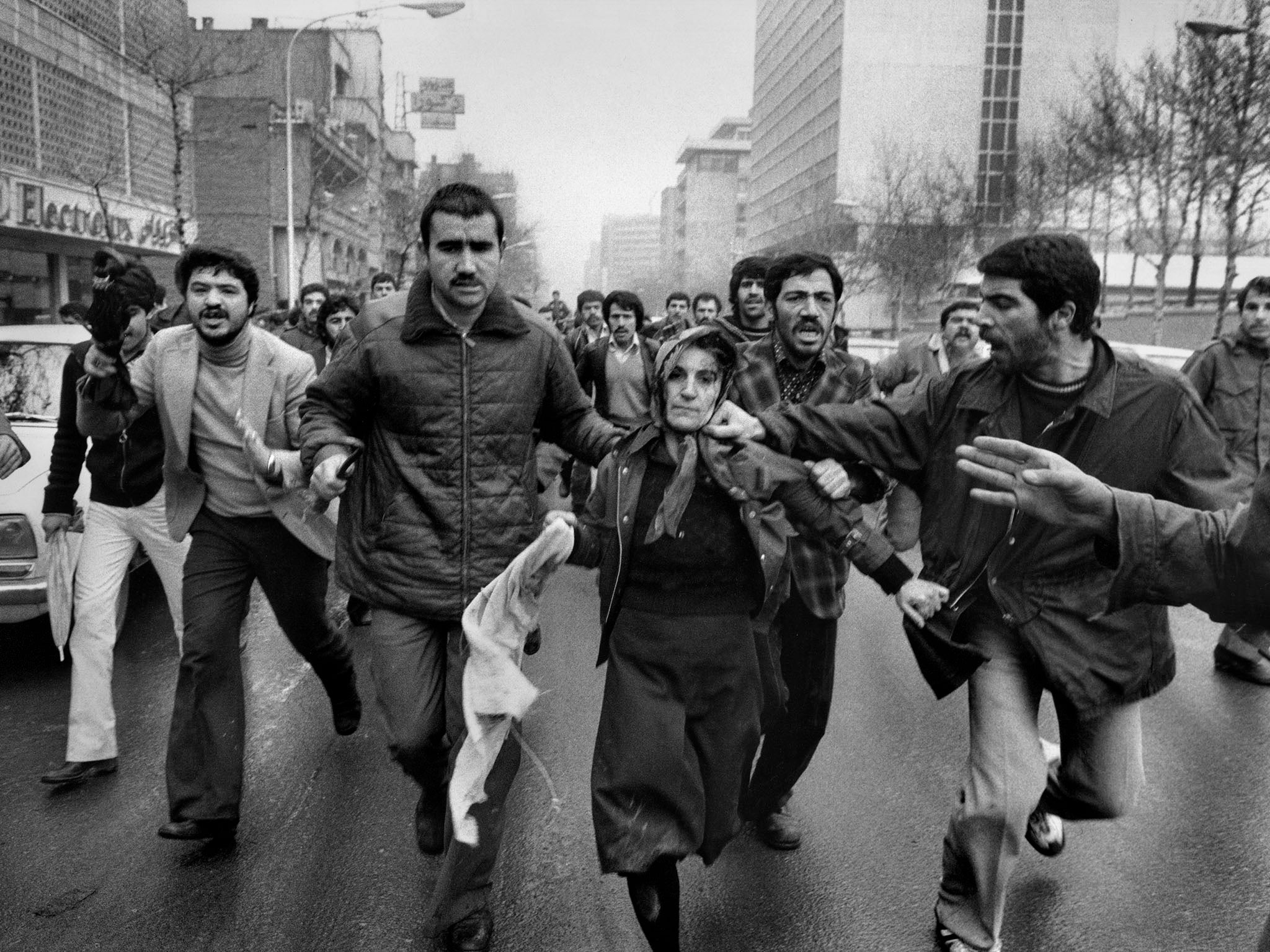

A group of male revolutionaries dragging a woman believed to be a supporter of the Shah through the streets. One has his fist pressed against her jaw.

Colleagues implored Abbas not to show the “negative side” of the revolution. He ignored them. He saw it as his duty to document the fact that the violence of the Shah’s forces was now being mirrored by zealous revolutionaries.

“I knew only once in my lifetime I would witness such a historical event,” he said. “I was not only concerned but I was also involved.”

Abbas’s lament that the revolution was “hijacked” is one that is familiar to many Iranians as is the observation that the advent of the Islamic Republic helped usher in an era of Islamism as a “world nuisance”.

“I could see that the wave of religious passion raised by Khomeini in Iran was not going to stop at the border of Iran,” Abbas said in 2009, in an interview with the British Journal of Photography. “It was going to spread in the Muslim world – and it did.”

In the following decades, Abbas – a resident of Paris throughout his later years – pursued his newly acquired fascination with religious motivations and actions, (in 2016 he published The Gods I’ve Seen, his study of Hindu devotees; his photographic essays also covered Judaism and Christianity).

Upon leaving Iran, he did not return for 17 years. It’s not fair to say his exile was self-imposed for his images had come to forge public memory of the Iranian revolution both for people in the country and the wider world. As such he was a known quantity to the authorities. He had peered into the Ayatollah’s soul through a lens and it wasn’t pretty.

But return he did. By the time of the election of Mohammed Khatami in 1997, he was curious to see how young people were responding to Islamic rule. These helped to form his 2002 book Iran Diary 1971-2001.

In the seventies Abbas – who once said that he had learned to see the world in black and white, that colour was a distraction – worked for the Sipa and Gamma agencies. He became a full member of Magnum in 1985; the credit “Abbas / Magnum” became his very brand, recognised by newspaper editors and readers alike as “a guarantee of both quality and humanity” as his colleague Phil Davison puts it.

Remembering his friend in Scotland’s Sunday Herald, Davison writes: “As a correspondent arriving alone in a strange country, often in a combat zone, it was always a relief to see Abbas and his camera in a doorway across the street, gesturing me to stay down and pointing out whence the gunfire was coming… If you wanted to get the story and get out safely, you stuck close to Abbas.”

Having taught himself how to operate a camera, Abbas got his first big break with the International Olympic Committee at the 1968 summer games in Mexico – he returned there in the early 1980s, where he spent years exploring the country. In 1992 he published Return to Mexico: Journeys Beyond the Mask.

One of the first photographs that gained him attention was of a white police officer in South Africa standing facing the camera in front of several rows of black trainees, heads shaven, bare-chested, wearing shorts – it became a widely used representation of apartheid.

In 1994, he published Allah O Akbar: A Journey Through Militant Islam, the culmination of his travels in Muslim countries.

Islamism, which he carefully distinguished from mainstream manifestations of the faith, remained a concern for him throughout his life – in 2009 he returned to the subject with In Whose Name? The Islamic World After 9/11.

That said, he was not afraid to voice uncomfortable truths about problems he believed were particular to Islam. “Islam has become a world nuisance,” he said.

“Christian, Jews, even Hindus, they have their own extremists and they’re as crazy as the others but… they don’t blow themselves up every day all over the world”.

“Muslims never fought Islamism,” he added. “In a way Muslims are hostage to the arguments of Islamism.”

“Christianity in a way lost its fundamentalism … with Voltaire. We’re hoping for a Voltaire in Islam.”

In the interviews conducted with him in French, English and Persian online, he comes across as a down to earth person with a sharp mind and zero pretension. He was also, clearly, a very private man.

Writing for BBC Persian, fellow photojournalist Hasan Sarbakhshian recalls a warning from Abbas: “Once people know who you are, it’s time to put the camera away”.

British-educated, Abbas was born into a Bahai family in the city of Khash in Sistan and Baluchistan state, near Iran’s border with Pakistan. In 1952 his parents moved to Paris from where they headed to Algeria. His father KH Attar and his mother Monavar Attar-Hamedani, were expelled along with other missionaries in 1968.

His own relationship with God, he told NPR, was professional. “He doesn’t tell me what to do, how to photograph – and I don’t tell him – how he should deal with his believers, you know. So we have a mutual respect relationship.”

In 2006 the Kayhan newspaper published an article under the title: “Abbas Attar, the black camera of a Bahai photographer”, after which he never returned to Iran. It accused him of being an “Islam-basher”, excoriating him as a Bahai with anti-Islam agenda – this of course was not true. Bahais are a persecuted minority in Iran. As he told Vice in 2015: "I’ve been more into photographing all the bullshit – and the good things – that people get up to in the name of God.”

Paying tribute to Abbas, Magnum president Thomas Dworzak said: “He was a godfather for a generation of younger photojournalists.”

Abbas, who was divorced, is survived by four sons and seven grandchildren. His advice to aspiring photojournalists was very practical: “Buy a good pair of walking shoes and fall in love. When you fall in love then you see things differently, then you become a photographer, but first get a good pair of walking shoes.”

Abbas Attar, photographer and journalist, born 29 March 1944, died 25 April 2018

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies